Point of View: Who’s Telling the Story?

Workshop Foundations

This month at The Writer’s Nest, we’re doing something a little different. Instead of diving straight into writing exercises, we’re laying the groundwork first, exploring the theory behind Voice and Point of View so that when we meet, we can spend our time where it matters most: in feedback, exploration, and practice.

What We Mean by “Point of View”

When writers talk about point of view, they’re not just talking about who’s telling the story, they’re talking about where the light falls.

Point of View (POV) decides what the reader can see, what they must imagine, and what they’ll never quite know. It’s both a camera and a conscience. Through it, we don’t just witness events, we inherit a bias, a vocabulary, a way of interpreting reality.

Every choice of viewpoint is a moral one: to align, to withhold, to reveal. The closer the lens, the more truth bends under the pressure of emotion. The wider it pulls back, the more we trade intimacy for clarity. Craft is the art of knowing when to shift that balance.

Every narrator is a doorway into the story’s moral architecture. First person can trap us inside obsession; third limited lets us feel its heat from across the room. Omniscient, meanwhile, is the god’s-eye view, generous but cold. The choice defines how truth feels, how much the reader can trust what they’re told, and how long that trust will last.

“I write almost always in the third person, and I don't think the narrator is male or female anyway. They're both, and young and old, and wise and silly, and sceptical and credulous, and innocent and experienced, all at once. Narrators are not even human - they're sprites.” Philip Pullman.

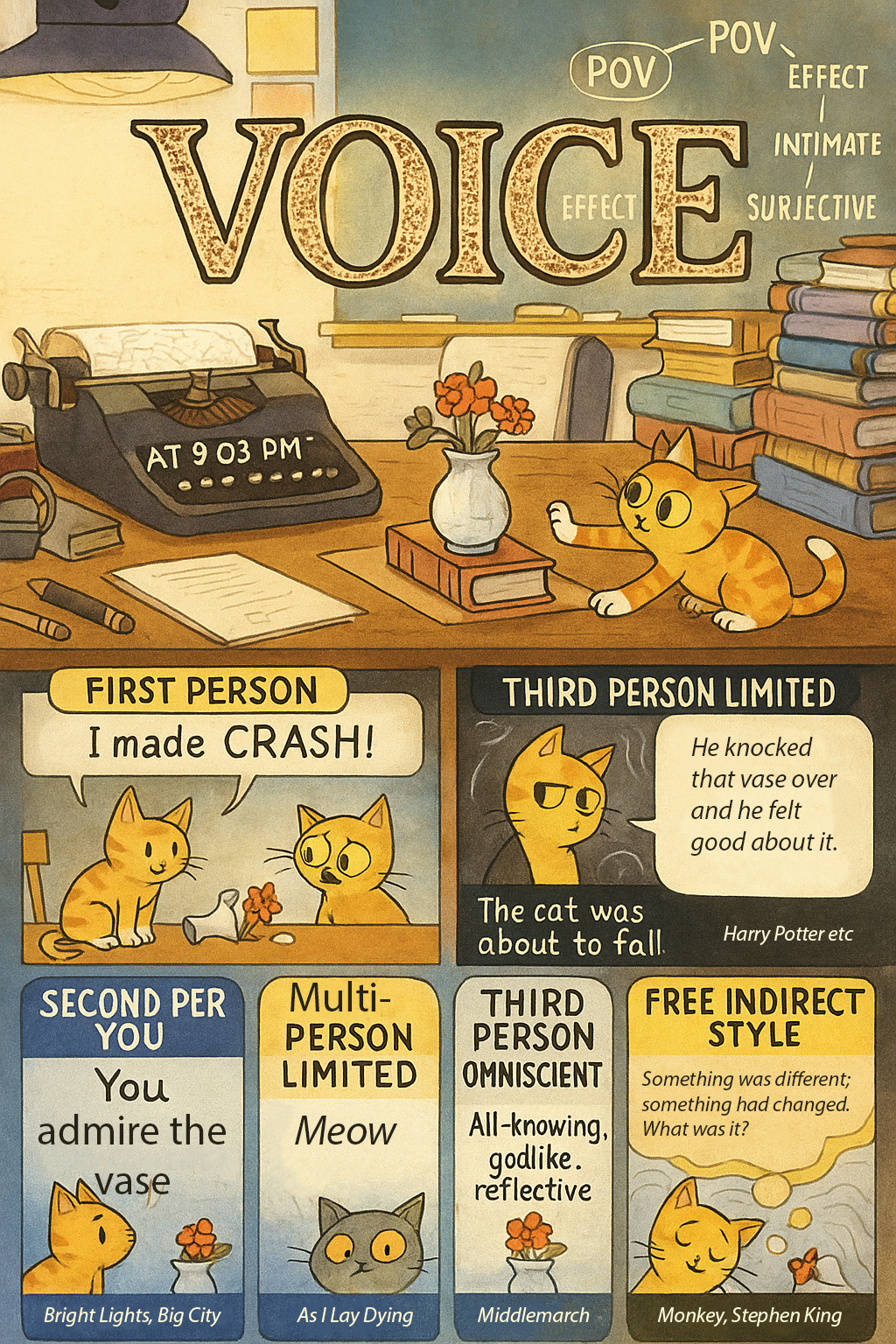

Points of view

The Many Eyes of Storytelling

Point of view isn’t just a technical choice, it’s the axis of perception around which a story turns. It decides who speaks, who sees, and how truth is filtered. Every story you’ve ever loved owes its power not just to what it tells, but who it lets you become while reading it.

“Point of view is the very essence of the art of fiction.”

Henry James – The Art of Fiction (1884)

Who’s Telling the Story?

At its simplest, POV answers one question: Through whose consciousness is the reader experiencing the world?

But in practice, that question multiplies endlessly. There are nearly infinite ways to deliver a story because every human perspective is partial, emotional, and unreliable in its own unique way.

The Classic Framework

POV Type Pronouns Effect Example

—————————————————————————————

First Person “I / we”

Intimate, subjective, often unreliable

The Catcher in the Rye

Second Person “You”

Immersive, direct, accusatory

Bright Lights, Big City

Third Person Limited “He / she / they”

Balanced distance and intimacy

Harry Potter

Third Person Omniscient “He / she / they”

All-knowing, godlike, reflective

Middlemarch

Free Indirect Style Blends character’s inner thoughts with third-person narration

Mrs Dalloway, Emma

——————————————————————————————

But these labels are starting points, not boundaries. Modern fiction plays with perception, bending and blending perspectives to capture the way human consciousness really feels; fractured, fluid, collective.

The Emotional Geometry of POV

Every point of view shapes emotional distance:

——————————————————————————

Close (inside consciousness)

Example: “I press my palm to the door; it’s still warm.”

Reader Effect: Empathy, immediacy

——————————————————————————

Medium (hovering nearby)

Example: “She pressed her palm to the door; it was warm.”

Reader Effect: Observation with feeling

——————————————————————————

Far (external or omniscient)

Example: “Her hand touched the door, and somewhere a fuse blew.”

Reader Effect: Reflection, detachment

——————————————————————————

Skilled writers adjust this distance mid-scene, zooming in for intimacy, pulling back for reflection. That dance between closeness and distance is one of fiction’s most powerful emotional tools.

First Person: The Mirror and the Mask

The first-person voice (“I”) is the most intimate of all narrative lenses, the most commonly used (currently), and the most deceptive.

It invites immediate identification; we see through the narrator’s eyes, feel their heartbeat, and adopt their logic without question.

That intimacy is also a trap. Every “I” hides blind spots. What a first-person narrator doesn’t notice is often more revealing than what they say.

Their worldview filters truth through bias, memory, and self-protection.

That’s why first person works so powerfully for stories of obsession, guilt, or trauma, we’re not just being told a story; we’re being confessed to.

“In the first person, the readers feel smart, like it's them solving the case.”

Patricia Cornwell

The Ego Trap

A common misstep among emerging writers is treating first person as a direct self-insert, writing the “I” as a thinly veiled version of oneself without reflection or transformation. The result is often what feels like a diary rather than a story.

Good fiction doesn’t simply replay experience; it reinterprets it. Writing “I” effectively requires distance, even if that narrator shares your history or emotions. The fictional “I” must exist as its own consciousness, capable of surprising you.

“Everyone is interesting except the narrator in a first-person story.”

William Kennedy

Craft-wise, first person lives or dies on voice. If the voice falters, the illusion breaks. You don’t have to like the narrator, but you must believe them.

Whether it’s Holden Caulfield’s caustic slang or Kazuo Ishiguro’s quiet repression in The Remains of the Day, the rhythm of their thinking becomes the novel’s heartbeat.

It’s also flexible in time. You can write:

First-person present for immediacy (“I run. The sirens grow louder.”)

First-person past for reflection (“I remember the night it began…”)

Or use dual first-person (like Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine) to explore contrast between inner and outer worlds.

In essence, first person is a mirror held at arm’s length, it reveals, but only from the angle the speaker allows.

Second Person: The Mirror Turned Outward

Second person (“you”) is rare, risky, and electrifying when it works. It makes the reader the protagonist, or sometimes, the accused.

Its power lies in disorientation. By saying “you”, the narrator reaches out of the page and implicates us. We become accomplices, witnesses, or replacements for the self the narrator can’t face. In Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney’s “you” blurs guilt and denial: the narrator speaks to himself but pretends he’s talking to someone else.

Second person can create:

Complicity — drawing readers into the act (You open the door, even though you know you shouldn’t.)

Distance — as if a character is watching themselves from outside (You watch her leave. You don’t stop her.)

Multiplicity — when “you” refers to an entire group (You Australians, You mothers, You who’ve lost someone), it becomes a chorus.

In flash fiction and short stories, second person can land like a jolt. In longer works, it’s best used sparingly and strategically, for letters, memories, instructions, or moments of confrontation. Too much, and the spell breaks; too little, and the reader forgets they were ever inside the skin.

Third person: My personal favourite

A narrative stance where the storyteller sits just outside the character’s skin, referring to them as he, she, they, Juliet, Niko, etc. The narrator may hover close as breath or far enough away to see the entire battlefield. Your job is to decide how close the camera gets and why.

THE THREE MAJOR FLAVOURS

Third Person Limited: One character’s lens at a time. We get their thoughts, biases, interpretations. We only know what they know. Great for emotional depth and unreliable shading.

Third Person Omniscient: A godlike voice with access to everyone and everything. It can jump minds, summarise years in a sentence, offer commentary, or deliver subtext the characters themselves miss.

Requires strong voice control to avoid feeling floaty.

Third Person Objective: A journalistic mode. No thoughts, no interiority, no opinion. Only observable action. Hemingway made this famous.

Terrific for tension and scenes where the reader must infer meaning.

MANAGING PSYCHIC DISTANCE

When we talk about psychic distance, we’re really talking about how close a reader feels to a character at any given moment. Not in a mystical sense, not in a “crystals on the windowsill” sense, it’s simply the proximity between the narrator’s voice and the character’s inner world.

THE SPECTRUM OF DISTANCE

External Distance: A wide shot. Behaviour, action, and what can be seen or heard. No thoughts unless externally implied. Useful for tension, mystery, restrained emotional beats.

Internal Distance: A close-up. Thoughts leak into the prose. Sensation and interpretation colour the world. Used for intimacy, complexity, and character-driven storytelling.

Most stories roam between these poles; the trick is controlling when and why.

And like most things in storytelling, this isn’t about right or wrong. It’s about control. It’s about choosing, moment by moment, how much access we’re giving the audience.

Imagine the narrator as a camera operator who happens to be very, very patient.

Sometimes they step back to take in the whole landscape.

Sometimes they move in close enough to catch the twitch of an eyelid.

The power lies in knowing when to shift.

The Wide Shot: You start far out. Cool, observational.

“Juliet crossed the street.”

That’s policy brief territory, clean, factual, zero editorialising.

This distance is useful when the story needs clarity. Structure. A sense of the world being bigger than one person’s heartbeat.

The Mid Shot: Move in a little closer.

“Juliet hesitated before crossing the street.”

Now we’re not just watching her; we’re reading her behaviour. We’re noticing something that might matter later.

This is where you build tension without shouting about it.

The Close-Up: Closer still.

“Juliet’s chest tightened as she stepped off the curb, wishing she hadn’t been seen.”

Here, the reader feels the character’s internal weather. Not just what she does, but how she experiences it.

This is where the emotional stakes live.

Inside the Character’s Mind: And then, when the story calls for it, we go right into the bloodstream.

“She shouldn’t have come. Not today, not like this.”

Now we’re in what you might call the Situation Room. We get access to the classified files. Thoughts, fears, judgements, the material the character doesn’t say out loud.

Use this wisely. You don’t want your reader feeling like they’re being briefed to death.

Why These Shifts Matter

A good writer uses psychic distance the way a good leader uses timing.

You zoom out to give context.

You zoom in to give impact.

And when you blend these shifts with intention, you create rhythm. You create emotional texture. Your story breathes.

If you stay too far away, readers won’t care.

If you stay too close, they’ll drown.

The art is in the movement, in the willingness to pull back, then lean in again, always in service of the moment.

The Trick Most Beginners Miss

Each distance has its own vocabulary.

The further away you are, the simpler the language.

The closer you get, the more subjective the world becomes.

When you master that subtle control of language, when your narrative distance matches the emotional temperature of the scene, that’s when your story starts sounding like it knows what it’s doing.

IN SHORT

Psychic distance isn’t just a tool. It’s a promise to your reader.

A promise that you’ll guide them, not shove them, toward what matters.

A promise that you’ll choose your closeness with care.

And a promise that when things get hard for your character, you won’t be afraid to let the reader lean in.

That balance, that measured generosity, is where great storytelling lives. And it’s something any writer can learn, one sentence at a time.

Beyond the Singular: Polyphony and Collective Voice

Mikhail Bakhtin introduced the idea of polyphony, the “many-voiced” novel. In truly polyphonic works, no single viewpoint dominates; instead, perspectives coexist and argue.

Think of Toni Morrison’s Beloved or Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, stories that refuse neat hierarchy. They create meaning through interplay, not authority.

Collective narrators (“we”) also have unique power: they speak for communities, cultures, or shared trauma. They create both inclusion and anonymity, a sense that identity itself is plural.

Terry Pratchett’s a fascinating case because, unlike Morrison or Smith, he rarely fractures his novels into overtly separate narrator, yet he absolutely masters the illusion of multiplicity. His “many voices” aren’t confined to chapters or first-person turns; they coexist inside the omniscient third.

Discworld novels, especially Night Watch, Small Gods, and Going Postal, demonstrate a kind of choral omniscience. The narrator moves between perspectives; a guard, a god, a street sweeper, without warning, yet each has their own rhythm and moral logic. He does this by:

Tonal modulation: He slides from satire to sincerity in a sentence, changing register as though the narrative voice itself is inhabited by many minds.

Free indirect discourse: Characters’ thoughts are folded into the narration without quotation marks or transitions, so the prose momentarily becomes them, especially in Guards! Guards! and Reaper Man.

Polyphonic worldview: Each novel contains entire philosophical camps (the cynics, the idealists, the bureaucrats) and Pratchett lets each one sound right in its own key. That’s many-voiced writing disguised as comedy.

He’s also unusual in that his narratorial voice has a distinct personality; the witty, compassionate, slightly weary observer who both mocks and loves humanity. Within that frame, he creates room for countless smaller voices to coexist. It’s like an orchestra with one wry conductor who occasionally joins in on the triangle.

Pratchett as the master of “omniscient polyphony” proves that a novel doesn’t need multiple first-person narrators to sound like it’s written by many souls at once.

And whether knowingly or not, I found myself drawn to this style of writing:

Dual Third-Person Limited: The Art of Strategic Concealment

In The Daemonica Symphony Series, (written as Eloisa Clark) I write in split third-person limited, alternating between two close perspectives, each filtered through their own emotional bias. It’s a stylistic choice, but also a structural one. By confining the lens to one consciousness at a time, I can let readers experience partial truths.

A carefully timed switch, stepping away from the character who’s lying, rationalising, or repressing, allows me to preserve mystery without breaking realism. The deception isn’t authorial; it’s psychological. Readers sense the distortion because they’ve been living inside that character’s head. When the viewpoint shifts, what was once certainty now feels suspect.

This creates a kind of narrative chiaroscuro, light and shadow made by proximity and distance. The story’s emotional truth comes not from any single voice, but from the friction between them.

The Power (and Danger) of Unreliability

Lolita is a 1955 novel that exemplifies the unreliable narrator.

Written by Russian and American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita’s protagonist Humbert Humbert seduces readers with eloquence while masking monstrous acts. His refined, witty prose manipulates sympathy, recasting abuse as tragic love. Nabokov uses Humbert’s charm as a trap: we’re drawn in by his intelligence, only to realise our complicity in his delusion. Through omission, self-justification, and performative confession, Humbert turns language into deception. The novel’s brilliance lies in this tension between beauty and horror, forcing readers to confront how easily style can distort morality, and how willingly we believe the storyteller we find most compelling.

The tension around Lolita lies in how it walks a razor’s edge, between exploitation and exposure. It isn’t written to glorify or romanticise paedophilia, but to dissect how language and charm can be used to justify horror. Its power is in that manipulation: we’re meant to be unsettled, not swayed. Anyone calling Lolita their favourite book should be ready to explain what they admire Nabokov’s genius with language, not Humbert’s lies.

Every narrator is biased. Some know they’re lying (Humbert Humbert). Some don’t (Nick Carraway - The Great Gatsby). Some may believe their own lies (Juniper Hayward - Yellowface) And some, like the plural “we” in Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, expose the impossibility of ever knowing the truth.

Unreliability is not a flaw, it’s a feature. It mirrors how humans experience reality: partial, interpretive, self-serving. Embracing this truth gives writers permission to play with contradiction and subjectivity.

Final Wrap

Point of view is more than a technical choice; it’s the skeleton of how a story thinks. Every shift in perspective changes what the reader believes, and what they’re denied. It shapes tone, empathy, and truth itself.

Writers often obsess over plot twists, but the deepest twist in any story comes from a change in perception, from standing somewhere new. Whether you’re slipping between dual third-person lenses, or staying locked inside one consciousness, remember that POV is not just how your story is told. It’s how your world is experienced.

Choose your lens with intent. Then write toward the edges of what that voice can see.

That’s where tension lives, in the half-lit spaces between knowledge and mystery, honesty and self-protection.

In the end, point of view isn’t about who speaks. It’s about who can’t.

Practical Craft: How to Choose and Control POV

Step 1: Write a single, simple event (max. 200 words). Something like:

“A man arrives in Paris.”

Step 2: Now, rewrite the same 200-word scene in three different POVs.

First Person Present Tense

Third Person Limited Past Tense

Either First or Third Person from another character’s perspective.

Something else entirely.

Step 3: Read them out loud.

Track what changes: language, empathy, pace, authority.

Notice what the reader learns and what they lose.

When selecting a POV, ask yourself:

Whose emotional truth is this story built on?

What do I gain, and lose, by seeing through this person’s eyes?

How much should the reader know versus feel?

Could the story become more complex if perception shifted midstream?

Next week at The Writer’s Nest:

We’ll explore our voices in our first attempt to write in alternative Points of View.

First Person, Third Person, Past Tense, Present Tense, the limitless opportunities available to us as writers to tell our stories.

Then we’ll ask: How do you choose? What impact does that choice make? What are the rules and how can you break them?

Join the Facebook group to get involved.